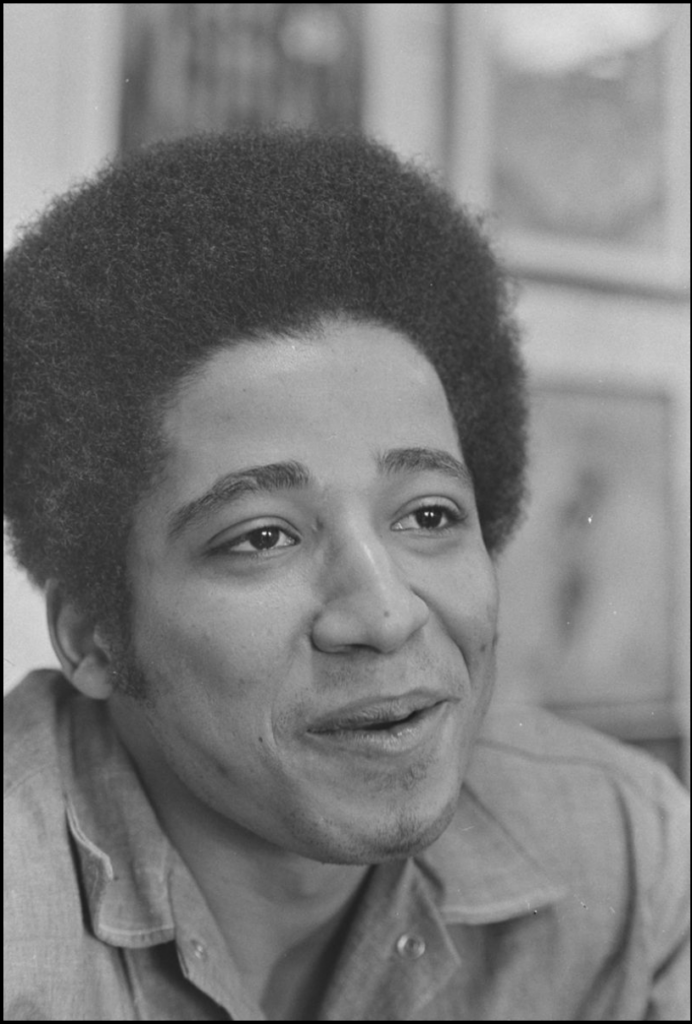

California prison officials consider him to be the most dangerous prisoner they’ve ever housed. His name still

strikes fear in prison authorities, even fifty years after his murder; and not just in California, but prisons across the nation, as even in death they fear his influence. Who is he? George Lester Jackson, prison number A63837, and this is his story.

$$$$$

Jackson’s family moved from Chicago to California in 1956, when he was 15 years old. A year later, he was arrested for petty theft and spent 7 months in the California Youth Authority.

In 1960, Jackson was arrested again, this time charged with second-degree armed robbery for robbing a Los Angeles gas station for $70; he pled guilty. In Jackson’s letters to family and friends, he claimed to be innocent of the crime, but says he pled guilty because he was promised a “short county jail term.” However, the sentencing judge, taking into account his previous convictions, instead sentenced him to state prison for a term of “one year to life.”

With this sentence, Jackson reasonably expected to be out in a year or two. After all, the crime was relatively petty, meaning no one got hurt. All Jackson would have to do is stay out of trouble so prison officials would document such. He was hopeful about getting out of prison, as he expressed in earlier letters to family members. He wrote about wanting better shoes so he could take care of his feet, which were sore, and he asked his father, a postal worker, to help him get a job once released. In an effort to remain trouble-free, he even avoided participating in work stoppages and other protests by his fellow prisoners. Despite this, officials noted him as “egocentric” and “antisocial,” and the board consistently denied him parole.

Because of Jackson’s indeterminate sentence, and the fact he was at the mercy of assessments and recommendations by guards, they, the guards, essentially determined whether or not he would ever be released from prison. And in the 1960s, when racism was prevalent, given that the majority of guards were white, things were not in Jackson’s favor. Jackson argued that, no matter what he did, guards perceived his behavior as “revolutionary,” which meant to prison officials he was rebellious and contemptuous toward authority. Whatever he did, or didn’t do, seemed to work against him. For example, his not participating in work stoppages was, according to guards, because he was strategically concealing his leadership of those very strikes. He was powerless to dispute the guards’ assessments, and because he pled guilty to the original robbery charge, he didn’t have a right to an attorney during his board hearings, nor was he eligible to appeal the original case. Eventually, Jackson’s hope began to vanish. As evident by the things he wrote about in his letters, he began to feel helpless and frustrated. He referred to prison guards as “pigs,” expressed his sentence was unjust, and that he was being oppressed. He began to proudly proclaim himself a revolutionary and often talked about escaping.

$$$$$

The 1960s was an extremely political time in America, full of civil rights and social justice movements. This wasn’t only the case on the outside, but in prison, too. Activism and revolutions took place. Prisoners began to protest, organize, and demand certain rights. They wanted to be heard in courts. They wanted freedom of speech and association, and overall better treatment. Much of the organizing among prisoners took place along racial lines, and if not in practice, certainly in the eyes of prison officials, the line between being a racially-based political movement or a race-based prison gang became blurred. According to Carl Larson, who worked as a prison guard during this period and later a warden, the civil rights and social justice movements outside of prison aligned with the more divided and radical revolutionaries inside prison: “We had this ‘revolution,’ and it manifested itself with a lot of rhetoric — in colleges and jails. The manifestation in colleges was mainly peaceful — a lot of rhetoric and thought. In the prisons, it manifested in a lot of violence.”

Jackson began studying radical political theorists like Karl Marx and Frantz Fanon around 1962, under the guidance of W.L. Nolen, another African-American prisoner who ran a reading group. Jackson would later say, “I met Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, Engels, and Mao when I entered prison and they redeemed me.” Jackson and other revolutionaries like Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton, Black Panthers who were also incarcerated in California during the 1960s, encouraged black prisoners to become conscious of the racial discrimination going on inside the walls. They closely studied revolutionary theorists and promoted violent political activity. “The concept of nonviolence is a false ideal,” Jackson wrote in one of these letters. And in another: “Politics is violence.” Ultimately, the members of this reading group, including Jackson and Nolen, would create the Black Guerrilla Family (BGF), which was founded sometime around 1966, and they aligned themselves with the Black Panther Party. According to the BGF and its followers, it’s a revolutionary political organization; according to prison officials, however, it’s a black prison gang. “The Black Guerrilla Family and the Black Panthers, they had a political side… but they were mostly gangs, mafia,” says Larson.

In January, 1967, Jackson appeared before the parole board and was denied again. “Of course, I could do the rest of my life in here,” he told his family, referring to his indeterminate sentence.

In December of 1967 he again appeared before the board. At the previous hearing they’d promised him that, if he gave them 7-8 months clean, he’d be granted parole. When he reminded them of this, they said, “We never make deals like that.” He was told he’d come back in a year.

In December of 1968, Jackson appeared before the board for the eighth time. After the hearing he was told by the institution employee who attends all his hearings that he’d been granted parole, and would be back on the streets March 4, 1969. He was excited and began telling everyone he had a “date,” that he’d finally be going home. He even wrote his family and asked them to prepare. Three days later, however, he was told a mistake had been made, and consideration had been postponed for another six months. He was told he’d be transferred to Soledad State Prison (from San Quentin), and if he did well for six months, he’d be paroled for sure. He stayed out of trouble, but when the June, 1969 hearing took place, he appeared before different board members. Of course, none of these board members could find any reference to the promise that had been made to him by the earlier board. He was denied another full year. Not surprisingly, Jackson’s frustrations were at an all-time high. And what would happen next would prove to be the breaking point.

Murder Season

In January, 1970, tensions at Soledad State Prison were rising among black and white prisoners, and also black prisoners and white prison guards. Jackson was housed in “Y” wing, and his mentor, W.L. Nolen was in “O” wing, which had been locked down off and on for months. Recently, Nolen had circulated a petition among the prisoner population; he wanted to file a lawsuit against guards for harassment, abuse, and the endangerment of black prisoners. Prison officials were not happy about this, and it was causing even further tension between them and black prisoners, especially Nolen, the author of the complaint. Nolen anticipated some sort of retaliation by guards; however, he didn’t know what would happen, or when.

On January 13, guards spontaneously released 15 prisoners from the locked-down “O” wing for yard. Seven were black, eight were white — each defined as racists by prison officials. Not surprisingly, a melee erupted. That’s when Opie Miller, a white officer who was manning the gun tower, shot into the melee, killing three prisoners: Cleveland Edwards, Alvin Miller, and W.L. Nolen — all black. Nolen was shot right through his heart.

Soledad prisoners demanded murder charges be filed against officer Miller, but three days later, the District Attorney announced it was “justifiable homicide,” and no charges would be filed. What seemed to be the targeting of W.L. and black prisoners raised questions about the motives of Miller, prison officials and the District Attorney. Later that night, John Vincent Mills, a white officer, was beat and thrown over the third tier, in “Y” wing. According to witnesses, there was an explosion of applause as the officer landed on the concrete floor, where he died. Prison authorities investigated the incident, and two weeks later charged those they claimed responsible: John Clutchette, Fleeta Drungo, and George Jackson.

By this time, Jackson was 28 years old. His one-year-to-life sentence looked like it was going to become a death sentence. The same DA who announced he would not be filing charges against the white officer who killed three black prisoners, announced he would be seeking the death penalty for the three black prisoners accused of killing the one white cop.

Jackson was transferred back to San Quentin and held in the Adjustment Center. The Adjustment Center, or “AC” as it’s often referred to, opened in 1960. It’s a 3-story-high building, and at the time was considered a state-of-the-art lockdown facility. Prisoners were locked down for 23 hours a day and had no other human contact other than shouting out the bars to the other 27 prisoners on the tier. When a prisoner would leave their cell, they would do so in shackles, and when they returned — escorted both ways — they would be strip-searched to ensure they weren’t smuggling anything back. Despite Jackson’s almost complete isolation, however, violence continued.

On February 25, 1970, Fred Billings, a black prisoner who was housed near Jackson in the AC, died suspiciously in his cell. Prison officials said he started his cell on fire and choked to death. Prisoner witnesses, however, says he was beaten by guards and tear-gassed to death. In any case, black prisoners saw this as another attack by prison guards.

In March, the very month after the suspicious death of Billings, a white guard at San Quentin was stabbed. He survived, but James McClain, a black prisoner, was charged with the stabbing.

Three months after that, in June, Jackson was scheduled to appear before the parole board, but refused to go. By now, he saw no point.

On June 28, Jackson wrote a letter to Joan, a friend and member of the Soledad defense team (who happened to be white) stating, “I’m thinking of Jon now.” Jon was Jackson’s 17-year-old brother. “I wish there was a way to talk to him in private. They ran him off, too.” Jackson was referring to Joan and Jon being denied visitation with him. “They certainly must be sure of themselves, I mean sure of being able to convict and hold and get rid of me, because they’re not very concerned with making me mad. And they know I’ll never forget.”

In July, William Schull, a white officer was killed while on duty at Soledad. Seven black prisoners were charged with the murder. And on July 28, Joan and Jon visited with Jackson.

On August 7, just a little over a week after Joan and Jon’s visit with Jackson, guards transported James McClain from San Quentin to the Marin County courthouse for the first day of his trial for stabbing the white guard. He was the first of black prisoners to stand trial on the attacks of white officers. By this time, McCain, along with the Soledad Brothers, had gained national support, thanks to Angela Davis, an assistant professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Jackson’s younger brother Jonathan, who had built the support by claiming the Soledad Brothers’ innocence and bringing publicity to the case.

The trial began and the first witness took that stand. Then, out of nowhere, Jon Jackson burst into the courtroom with a pistol and a carbine rifle. With the help of McClain and two other prisoners, William Christmas and Ruchell Magee, who were there to testify for McClain, Jon took the judge, Harold Haley, District Attorney Gary Thomas, and three jurors’ hostage, demanding release of the Soledad Brothers. They put the hostages into a rented van, and according to eyewitnesses, fastened a shotgun to the judge’s neck with adhesive tape and some sort of strap, so it pointed directly under the judge’s chin. By now, the Marin County police arrived and joined forces with San Quentin guards, and when the van began to pull out of the courthouse parking lot, they unloaded a flurry of bullets into it, killing Jackson, McClain, and Christmas. The judge was also killed, though it’s unclear if it was from police fire or the shotgun taped under his chin. The DA was permanently paralyzed. Ruchell Magee and the jurors survived and the event made national headlines.

As of August 7, the total amount of deaths both inside and outside of prison: 10.

The guns used by Jon were eventually traced to Angela Davis, who’d purchased them legally over the previous two years. She became a fugitive until October when she was caught and put in jail. (She eventually stood trial in 1972 for the kidnapping and murder of the judge, but was acquitted by an all-white jury.)

George Jackson remained in San Quentin’s Adjustment Center while awaiting trial for the murder of officer Mills. In the fall of 1970, he released his first book, Soledad Brother, which he dedicated to his brother Jonathan. The book is a collection of letters he’d written to his mother, father, siblings and lawyers between the years of 1964 and 1970. Soledad Brothers received critical acclaim and was compared to books like Autobiography of Malcolm X and Soul on Ice, written by Black Panther and prisoner Eldridge Cleaver. The final letter in Soledad Brother is addressed to Joan and dated August 9, 1970 — two days after Jon was killed by police. It reads in part: “I want people to wonder at what forces created him, terrible, vindictive, cold, calm man-child, courage in one hand, the machine gun in the other, scourge of the unrighteous — an ox for the people to ride!!!…I can’t go any further, it would just be a love story about the baddest brother this world has ever had the privilege to meet, and it’s just not popular or safe — to say I love him.”

1971: Jackson’s legal team was hard at work in preparation of his upcoming murder trial which was set to begin August 24. In April, Jackson’s legal team filed a complaint that prison officials were interfering with his defense by hiding and paroling witnesses favorable to him, and threatening others into testifying against him. Several prisoners wrote declarations confirming these claims.

By August, one year had passed since Jon was killed, and Jackson completed a second book of letters and essays titled Blood in My Eye. (This book would not be published until the following year.) He also had a substantial legal team and was nationally known as one of the Soledad Brothers.

On August 18, Jackson rewrote his will, leaving all royalties and control of his legal defense fund to the Black Panther Party.

What happened next, however, remains somewhat of a mystery, even to this day, full of contradictions, controversy and conspiracy theories, but it goes something like this…

The Dragon Has Come

On Saturday, August 21, at around 2pm, attorney Stephen Bingham arrived at San Quentin for a scheduled visit with Jackson. Bingham, who came from a wealthy family in Connecticut, was exactly the same age as Jackson: 29. He was a graduate of Boalt Hall Law School at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with Bingham was Vanita Anderson, an “investigator” for the defense team. She brought with her a tape recorder, and Bingham had with him a bunch of legal papers, as well as the galleys (typeset pages) of Jackson’s new book. Both Bingham and Anderson consented to a search of their persons and items, and according to a Washington Post article that would be published a few days later, Bingham passed through a metal detector and a guard inspected the tape recorder’s battery case.

Anderson was ultimately denied entry because she had already visited Jackson earlier that week, and a day prior to this (on August 20), James Park, the Associate Warden (AW) at San Quentin during this time, issued a new policy limiting “reporter” interviews of prisoners in “lockups,” like the AC, to once every 90 days, due to the enormous amount of attention “famous” prisoners like Jackson were getting. Whether Anderson was an investigator for the defense team or a reporter is unclear. In any case, Bingham was Jackson’s lawyer, so his visit could not be denied and he was allowed entry.

According to Bingham, after the guard on duty searched the tape recorder and determined nothing was in it, he encouraged Bingham to take it into the prison since Anderson was denied entry. But Carl Larson, who at the time was working as a correctional counselor at Chino State Prison and recalls discussing the day’s events with AW Park, says, “When Bingham came into the prison, he had a tape recorder, he was going to visit with George Jackson, and the officer at the gate wanted to take the tape recorder apart. The lawyer argued, got offended, resisted, asked for a supervisor. The officer calls a lieutenant, says, ‘You can’t come in with that.’ The officer calls Jim Park, and Jim Park approved it, said, ‘Let it go in.’”

Once Bingham was allowed into the prison, guards escorted Jackson to the room where his visit with Bingham was to take place. Jackson sat across from Bingham at a wooden table that had no barriers, and guards intermittently checked on the two. The meeting only lasted about 15 minutes, then Bingham left with tape recorder and papers in hand.

Around 2:25pm officer Frank DeLeon escorted Jackson back to the AC, where officer Urbano Rubiaco began to strip-search Jackson before letting him back to his cell. Reportedly, Rubiaco asked Jackson about what appeared to be a pencil or something in his hair, and that’s when Jackson pulled out a gun, inserted a clip and pointed it at officers. He then shouted “This is it!” and ordered officer Rubiaco to open all of the prisoners’ cells, where he and other black prisoners took hostage all four guards’ (officers Frank DeLeon, Paul Krasnes, Kenneth McCray, and Charles Breckenridge), and two white prisoners (John Lynn and Ronald Kane). Sometime while this was going on, sergeant Jere Graham arrived at the AC to assist officer DeLeon on another escort, unaware of what was taking place, and when he arrived, he, too, was taken hostage. Jackson reportedly yelled, “The dragon has come!” — a reference to a poem written by North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh about the power of imprisonment to generate a revolution.

During the revolt, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, officer Breckenridge had his throat slashed and was dragged to Jackson’s cell. He survived, but officers DeLeon and Krasnes, along with Lynn and Kane, the two white inmates, were killed, and their bodies thrown on top of Breckenridge. Sergeant Graham was also killed, though it’s unclear where his body was left.

When prison officials who were not in the Adjustment Center became aware of what was going on, they alerted the California Highway Patrol and Marin County Sheriff who came heavily armed and blocked all access roads to the prison, demanding prisoners give up. Jackson reportedly yelled to his fellow participants, “It’s me they want!,” so with gun in hand, along with Johnny Spain, another black prisoner, he ran out of the AC, where he was immediately gunned down by a marksman; Spain ducked for cover under a bush. There are conflicting stories about how many shots Jackson suffered, and exactly where he was shot. Most say Jackson was shot in the back and the bullet ricocheted off his spine and came out his head. Others say the bullet traveled the other way. Soledad Brother John Clutchette says Jackson was shot in the back by the guard in the gun tower, then when guards gathered around him, they shot him again, in the head. However Jackson was shot, he died quickly.

When guards finally entered the AC they found a bloodbath where the revolt had taken place. Three guards and two prisoners, all who were white, had been shot and/or stabbed to death. Breckenridge, of course, had his throat slashed, but survived. Messages were found in Jackson’s cell that said, “Take the bullets out the bag,” and “Hurry and give me the piece in the bag. Keep the bullets.”

According to historian Dan Berger, the guards then retaliated by stripping, handcuffing, and hog-tying the remaining 26 prisoners in AC, and left them naked in the San Quentin yard next to where Jackson laid dead. During the following days they were repeatedly interrogated and beat. Warden Louis S. Nelson reportedly told them, “None of you will ever leave here alive.”

$$$$$

What exactly happened on August 21, 1971, we may never know. California correctional authorities have their version, prisoners and Jackson supporters have theirs, and journalists and investigators have theirs, which usually lies somewhere in the middle. Prison officials will usually tell of Jackson’s attempt to escape, claiming his lawyer, Bingham, smuggled him in a gun and an afro wig to hide it under, inside the tape recorder. Some Jackson supporters claim he was not trying to escape, but instead was set up for assassination by the Criminal Conspiracy Section of the Los Angeles Police Department, who had infultrated the Black Panthers in Los Angeles and the Bay Area in an attempt to track and control the revolutionaries. Others say Jackson was set up as an escape attempt so “they” could kill him for the murder of officer Mills, and because of the power and influence he’d gained over other black prisoners, who’d been assaulting and killing white prison guards.

There’s credibility to the theory Jackson was attempting to escape. After all, he openly spoke about doing so. Then again, with close enough examination of all the evidence, the other theories are possible as well. Regardless of what happened, however, the stories by prison officials are plagued with inconsistencies — including what should be hard facts, which is particularly troubling. For example, the type of gun Jackson was said to have had often changed. Some said it was a .25, others said a .38, and others said a 9mm Astra M-600 semiautomatic pistol. How can this not be clear? The 9mm Astra seems to be what most have settled on, but what’s strange about this is that a 9mm Astra M-600 is 9 inches long, weighs over two pounds and is nicknamed “The Pipe wrench”; something probably impossible to conceal under an afro wig, or inside a tape recorder. (Many say it most certainly would not have fit.) Daniel P. Scarborough, the officer who was responsible for processing Bingham, later tried to clarify what happened by saying Bingham concealed the gun between stapled pieces of paper. I guess only Bingham truly knows whether or not he smuggled the gun and afro wig into Jackson that day, and if he did, how he did it. Immediately after the incident, he went on the run, fleeing the country for 13 years. He returned in 1984, however, to stand trial, argued guards had brought Jackson the gun, hoping he’d be killed. Bingham was acquitted of all charges relating to the August 21, 1971 event in 1986. (There are theories that the gun had been smuggled into Jackson in pieces, over time, where he was able to put it together himself. Could the “pencil” officer Rubiaco thought he saw in Jackson’s hair have been a barrel? The notes later found in Jackson’s cell lend some credibility to the theory Jackson had the gun, or at least some of it, before August 21.)

Six prisoners were ultimately charged in the events that took place in the Adjustment Center: Fleeta Drumgo, one of the original Soledad Brothers; Luis Talamantez; Willie Tate; David Johnson; Johnny Spain; and Hugo “Yogi” Pinell. Drumgo was acquitted of all charges and paroled shortly after. However, he was shot to death in 1979, in Oakland, under mysterious circumstances. There were reportedly two shooters, neither of whom have been caught. Talamantez and Tate were acquitted on all charges and paroled sometime in the 1970s. Johnson was convicted on one count of assault for strangling officer Breckenridge, but was also paroled sometime in the 70s. Spain was convicted on two counts of murder for killing officers DeLeon and Graham, but the conviction was overturned in 1982, and he paroled in 1988. Pinell was convicted on two counts of assault for slashing the throats of officers Breckenridge and Rubiaco, both of whom survived, and remained in solitary confinement until he was murdered under controversial circumstances in 2015. These men became known as the “San Quentin Six,” and the trial, which cost over 2 million dollars and lasted over 16 months, was dubbed “The Longest Trial” by Time magazine. It took the jury 124 days to deliberate, and when the verdicts came in, it took Judge Henry J. Broderick 24 minutes to read them.

Jackson’s legacy lives on today through prison lore, not only in California, but across America. Prisoners, especially black, tend to view him as an inspiration: a man who, come what may, stood up for his people against a racist, oppressive, and abusive systems. To them he is a martyr. To prison officials, however, he is the most dangerous prisoner ever housed in California. He is a terrorist. Jackson was “a sociopath, a very personable hoodlum” who “didn’t give a shit about the revolution,” says San Quentin’s Associate Warden James Park. Today, even the slightest association with Jackson can lead to discipline for prisoners, such as being validated as a member of the Black Guerrilla Family, or in the case of Stanley “Tookie” Williams, being used to justify an execution. (Williams, co-founder of the Crips who turned outspoken advocate for nonviolence, and who had been on San Quentin’s death row since 1981, sought clemency from Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2005. Governor Schwarzenegger denied the petition, however, at least partly because Williams included Jackson in the dedication of one of his books. Williams was executed on December 14, 2005.) But not only in prison does Jackson’s legacy live on. In 2003, rapper Ja Rule titled his album Blood in My Eye in homage of Jackson and his bestselling book. Even Bob Dylan released a single in which he titled George Jackson, and several other musicians have paid homage as well.

In 2007, the movie Black August, which recaptured the last 14 months of Jackson’s life was released. Jackson has also been acclaimed throughout the world as one of the most powerful and eloquent black writers.

To this day, nearly 50 years later, on the path to the prison yard at San Quentin, an American flag perpetually flies at half-staff to commemorate August 21, 1971, the deadliest day in California prison history.

About the Author: Mike Enemigo is America’s #1 incarcerated author, with over 25 books published and many more on the way. He specializes in writing about prison, street crime, and how-to info for prisoners. Learn more at thecellblock.net, where you can subscribe to his blog; there, he provides raw, uncensored news, entertainment and resources on the topics of prison and street-culture from a true, insider’s perspective. You can also follow him on IG @mikenemigo, and Facebook at thecellblock.net and thecellblockofficial.

1 Comment

This author like so many others make the mistake of saying that George Jackson founded the BGF. George Jackson was not the founder nor a member of the BGF in fact the group did not come into existence until after Jackson’s death.