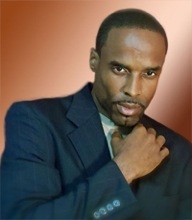

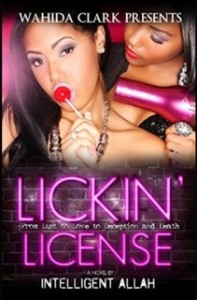

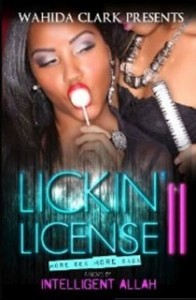

From inside the belly of the beast Intelligent Allah forged his pen game by going through trials and tribulations that would have crushed the average joe. From his misadventures in the streets of New York City and the drug game to his survival in the vicious New York penal system, Intelligent Allah has thrived and been successful in any and all avenues that he has pursued. From the netherworld of corruption and violence Intelligent Allah reached out to the world, using his writing talents to network, build bridges and make a name, career and future for himself while still incarcerated. And now his future is here as he is out in the world and ready to take it on. You know him for his urban sex bangers- Licken’ License I and II, published by Wahida Clark Presents, but let’s take a look back at how Intelligent Allah got where he is today. This is the Gorilla Convict exclusive with the freshly released novelist, who reentered society after almost two decades in prison. Check it out-

From inside the belly of the beast Intelligent Allah forged his pen game by going through trials and tribulations that would have crushed the average joe. From his misadventures in the streets of New York City and the drug game to his survival in the vicious New York penal system, Intelligent Allah has thrived and been successful in any and all avenues that he has pursued. From the netherworld of corruption and violence Intelligent Allah reached out to the world, using his writing talents to network, build bridges and make a name, career and future for himself while still incarcerated. And now his future is here as he is out in the world and ready to take it on. You know him for his urban sex bangers- Licken’ License I and II, published by Wahida Clark Presents, but let’s take a look back at how Intelligent Allah got where he is today. This is the Gorilla Convict exclusive with the freshly released novelist, who reentered society after almost two decades in prison. Check it out-

Describe where you have been locked up at and for how long?

I’m from East New York, Brooklyn and I caught my case there, so I was locked up in New York state for 18 1/2 years. My sentence was 19 years to Life, but I got out six months early for a Limited Credit Time Allowance–what is essentially good time. I first hit Rikers Island in 1994. I was 17 so I was in the adolescent building, which is C-74. A lot of people know of the line Kool G. Rap spit on the song Rikers Island, “C-74/Adolescents at war.” That line was from a saying that started on The Island because it was war doing down in C-74. It was the wildest spot on The Island, because young dudes are generally wilder. So every day there was cuttings and sometimes stabbings. Most of the drama was over the phones, because if you wasn’t among the team regulating the house or you paying in drugs or commissary, you generally wasn’t touching the phone. Heads were getting cut in the messhall, the yard, the school, the visiting floor–it was popping off everywhere. It was nothing to see a trail of blood in the corridor or to have somebody run past you bleeding and it leak on you. When I turned 19, I went to North facility, which is an adult building. As soon as I walked through the door into the house I was assigned, a female C/O told me, “I hope you’re not bringing no trouble to this house. You ain’t in adolescents no more.” And she was right, because the adults were far more laid back. Stuff was popping off, but nowhere nearly as much as when I was in C-74. I was in C-74 for about 14 months and in North Facility for about two months.

When I went Up North, I was in Downstate for a minute, which is where they send people temporarily to be classified and shipped off. That was a really different type of atmosphere, because you because most dudes are coming Up North for the first time and trying to wrap their minds around doing the time they were sentenced to. For me that meant coming to terms with the dynamics of doing 19-Life at age 19. Recreation was limited, so we were in our cells most of the day. That was the beginning of me really analyze where I went wrong, running the streets at age 13.

After I left Downstate I hit Sing Sing. This prison is infamous and for good reason. It was like being back in C-74 with the adolescents, literally. That’s because many of the dudes I was in C-74 with were coming to Sing Sing and bringing a lot of the beef they had with them. And Sing Sing was popping anyway, because its only about an hour from New York City and there are a lot of officers working there who live in the five boroughs. So there was drugs there on the regular flowing from visits and officers who know guys locked up there. And of course, drugs are a source of beef in prison just like in the streets. Sing Sing is also one of the few prison where you’ll see a majority of black and Latino officers working instead of the majority being white. And you have some dime pieces working there, and some freaks that were down for whatever. So that was a unique dynamic. There was a prostitution rink going down that lead to some officers losing their jobs. Things were just always going down in Sing Sing. I left in late 1995, right before a brother was stabbed to death.

After I left Downstate I hit Sing Sing. This prison is infamous and for good reason. It was like being back in C-74 with the adolescents, literally. That’s because many of the dudes I was in C-74 with were coming to Sing Sing and bringing a lot of the beef they had with them. And Sing Sing was popping anyway, because its only about an hour from New York City and there are a lot of officers working there who live in the five boroughs. So there was drugs there on the regular flowing from visits and officers who know guys locked up there. And of course, drugs are a source of beef in prison just like in the streets. Sing Sing is also one of the few prison where you’ll see a majority of black and Latino officers working instead of the majority being white. And you have some dime pieces working there, and some freaks that were down for whatever. So that was a unique dynamic. There was a prostitution rink going down that lead to some officers losing their jobs. Things were just always going down in Sing Sing. I left in late 1995, right before a brother was stabbed to death.

Next I hit Comstock (Great Meadows Correctional Facility in Comstock, New York), which is about five hours from New York and regulated by straight racist hillbillies. Officers were beating dudes up on the regular and planting drugs and weapons on them. I watched a dude get beat up with night sticks minutes after I walking in, because he moved his hand from the wall when he was being pat frisked. The officers there cultivated an atmosphere of oppression. You had to walk in total silence through the halls, or risk being jumped by a group of tobacco-spewing rednecks that would be scared to walk pass the same dudes in society. The men locked up in Comstock were also just as wild. They were mostly adolescents. It was going down regularly, more than Sing Sing and just a little less than C-74. They used to call Comstock Gladiator School, and the spot earned that name.

After Comstock, I hit Green Haven. That’s just about 90 minutes from NYC. I was fairly laid back when I was there in 1996. But it was not a spot to sleep on, because the nature of prison is volatile. Years earlier a female officer was murdered and by all accounts among men in prison, her coworkers did it and blamed it on a guy doing time there. He’s still inn the Box (23-hour lock down) right now. After I left Green Haven, one of the captains, a straight asshole, was stabbed up by a Muslim brother named Mailik. The Captain had denied Malik’s request to attend his mother’s funeral. He was denied for some bogus reason. That hardly never happens. The captain was walking in the yard with an officer and Malik gave it to him with two homemade knives. He brought all of the bitch out of the captain and the officer who ran and came back with some other officers, pleading for Malik to stop. So Green Haven was the type of prison that serves as a reminder doing time is not a game and anybody can get it.

After Comstock, I hit Green Haven. That’s just about 90 minutes from NYC. I was fairly laid back when I was there in 1996. But it was not a spot to sleep on, because the nature of prison is volatile. Years earlier a female officer was murdered and by all accounts among men in prison, her coworkers did it and blamed it on a guy doing time there. He’s still inn the Box (23-hour lock down) right now. After I left Green Haven, one of the captains, a straight asshole, was stabbed up by a Muslim brother named Mailik. The Captain had denied Malik’s request to attend his mother’s funeral. He was denied for some bogus reason. That hardly never happens. The captain was walking in the yard with an officer and Malik gave it to him with two homemade knives. He brought all of the bitch out of the captain and the officer who ran and came back with some other officers, pleading for Malik to stop. So Green Haven was the type of prison that serves as a reminder doing time is not a game and anybody can get it.

Next I went to Elmira, back Up North about five hours away. There were a bunch of racist officers just like Comstock and a bunch of adolescents like Comstock. But Elmira was definitely the wildest spot I had been during my bid. This was where I saw the most riots and violence overall. It was also the first place I saw a dude get “burnt out,” meaning his cell was put on fire so he would be forced to leave the cell block.

After Elmira I went Shawangunk. It was about an hour and a half from NYC and pretty laid back. Most of the violence came in the form of fights. Stabbings and cuttings were rare. I met a lot of good brothers in Shawangunk. It’s where I first really became conscious of the Prison Industrial Complex and the effects of incarceration on people in society. It was here I became a member of the editorial board of The Lifer’s Call, which was a newsletter put out by the Lifer’s & Long Termers’ Organization. There was a high level of consciousness within the prison.

Next I went back to Elmira. This time the prison had calmed down some. Most people attributed to there now being the privilege of televisions in the cells, so a lot of heads were inside watching TV instead of running the yard getting into beef. But while the violence overall had slowed, there was an increase in the gangs.

After Elmira was Coxsackie (pronounced Cacksacki) This spot was crazy, more adolescents than any other and the officers treated everyone like kids. It was constant searching, officers disrespecting guys verbally and physically. Basic privileges like being about to take a pen to the yard were prohibited. I had challenged that, because I needed to converse and strategize with my lawyers on the phone. I was only there for 33 days and I had about seven grievances challenging the prison conditions.

After Elmira was Coxsackie (pronounced Cacksacki) This spot was crazy, more adolescents than any other and the officers treated everyone like kids. It was constant searching, officers disrespecting guys verbally and physically. Basic privileges like being about to take a pen to the yard were prohibited. I had challenged that, because I needed to converse and strategize with my lawyers on the phone. I was only there for 33 days and I had about seven grievances challenging the prison conditions.

Next I ended up in Napanoch (Eastern Correctional Facility in Napanoch, New York). It’s about an hour and a half from NYC. This prison was totally different. Almost no violence, plenty of positive programs to get in like college and the poetry group I joined called Harvest Moon. The officers were mostly older white dudes and very laid back. The guys doing time there were laid back, because most didn’t want to risk getting kicked out of the spot and sent Up North. Some people called the prison “Happy Nap.” What was probably most important to me about Nap, was there were so many people there writing–and several published or were published later. My comrade Great Zach Tate (Johnny Hustle, No Way Out, Lost & Turned Out), Casino Mike (2 Sides 2 A Story), Fee G. Heyward (Game Like Honey, I-Con), Tha Twinz (Crime Pays? and Crime Pays 2)–the list goes on. It was also in Nap where I got my first publishing credits for articles and editorials. I also met my publisher Wahida Clark during this time and earned my first contributing editor credit for working on her book Thug Matrimony. So my time at Nap was very productive.

After I left Knap, I went to Woodbourne, which is a medium security prison. This was a drastic change for me psychologically, because it signaled my having just six years left before I was eligible for parole. Mind you, when I came up, I had over 18 left. Woodbourne is close to NYC and was relatively drama free, with the exception of a few fights and rare stabbing. I met the rapper Shyne there. He was a laid back dude who stayed to himself mostly as he prepared to go home. What also kept Woodbourne drama free was the snitch system. It was serious. Guys would get into a fight, get away with it, then days later get snatched up by officers. A lot of guys in prison were known for buying drugs from multiple people, running up tabs and not paying up front, then they would voluntarily go into Protective Custody claiming the guys who sold them drugs were going to hurt them. Well in Woodboure, that type of thing happened with not only guys buying drugs, but guys who owed other dudes for commissary. Another thing that made the spot laid back were lazy officers. Most of them were overweight and too lazy too search men. It was a regular event for them to be laid back with their feet kicked up and sleeping in recreation or a cell block. And there were times they would shut the prison down and lock us in so they could have parties and celebrations. Another contributing factor to the prison running smoothly was there were a lot of positive programs for men to engage in. But the harshest thing about Woodbourne was watching men who had transformed their lives and were ready for society, only to be hit by the parole board based on the nature of their crimes–which is something that will never change. It seemed like no matter how good a record or how many accomplishments guys had, the parole board would still hit them. It was clearly a financial thing, because people in prison mean jobs for rural communities in Upstate, New York that have no means of income, because the major industries in New York are centered in NYC. I read an article once that mentioned child in church praying that a prison be built in his Upstate neighborhood. Statistically, people who serve 10 years or more and people who have college education are the least likely to return to prison, but these are the guys who are hit the most by the parole board if they have a violent crime. I was fortunate, because in spite of all of this, I went to the parole board for the first time at Woodboure and was granted my release.

After that, I spent about a month in Queensboro, which is a minimum security prison for guys about to go home and guys who are serving short stays for parole violations. This spot disgusted me. There we so many dudes there with childish mentalities, doing stuff that was annoying and would get them stabbed in a spot like Comstock or Sing Sing. I remember I was in this class designed to help prepare guys for release. It was primarily a bunch of information I knew and had actually taught to other men Up North, but this class was being taught by a black woman who actually had an interest in seeing guys do good. But she couldn’t teach the class, because you had grown ass men farting in class, making outbursts, laughing like little girls and a whole bunch of other childish things that like I said would have gotten them stabbed in Comstock or Sing Sing. Tolerating this made my stay at Queensboro a rough one. Then, because no one stayed there long, the living conditions of the prison were crazy and the prison administration didn’t follow state regulations completely. The only thing that kept me focused was the reality that I had one foot out of the door.

After that, I spent about a month in Queensboro, which is a minimum security prison for guys about to go home and guys who are serving short stays for parole violations. This spot disgusted me. There we so many dudes there with childish mentalities, doing stuff that was annoying and would get them stabbed in a spot like Comstock or Sing Sing. I remember I was in this class designed to help prepare guys for release. It was primarily a bunch of information I knew and had actually taught to other men Up North, but this class was being taught by a black woman who actually had an interest in seeing guys do good. But she couldn’t teach the class, because you had grown ass men farting in class, making outbursts, laughing like little girls and a whole bunch of other childish things that like I said would have gotten them stabbed in Comstock or Sing Sing. Tolerating this made my stay at Queensboro a rough one. Then, because no one stayed there long, the living conditions of the prison were crazy and the prison administration didn’t follow state regulations completely. The only thing that kept me focused was the reality that I had one foot out of the door.

Describe the conditions of the prisons you have resided in?

I covered most of the prison conditions in the question above. Prisons are oppressive places, be it oppression at the hands of people incarcerated or people working there. The food is ridiculous and I was going through hell, because I’ve been a vegan since 2001. The health care is one of the worse things about prison. That helped keep me focus on maintaining optimal health. I’ve seen guys be misdiagnosed or not diagnosed at all. Guys would have to fight constantly to receive simple screening to determine what the source of their medical problems were.

Describe the gang problems inside the New York Department of Corrections and how it changed during your incarceration?

I watched gangs really expand in New York State since I was on Rikers Island in February 1994. The big numbers then were mostly in Latino gangs like La Familia, Latin Kings and Nieta. I remember them having entire houses in C-74 locked down, to where a lot of black dudes were scare to go there because you couldn’t get on the phone unless you were down with them or real cool with them. And at this time, The Bloods were growing, so they were constantly going at it with the Latino gangs. That same drama followed them Up North. I saw it play out in Sing Sing and Elmira–beef between Bloods and Latin Kings on the Island that led to a riot in Sing Sing and a riot in Elmira.

How did you occupy your time during your incarceration or what positive pursuits did you pursue?

How did you occupy your time during your incarceration or what positive pursuits did you pursue?

I did too many things to name. A lot of my time was spent reading and studying everything from African history and stocks, to the publishing industry, diet and nutrition. I had been into poetry and rapping before I was arrested, but inside I began writing through challenging the administration and fighting in court. That led to me writing editorials and articles and ultimately fiction after I took a creative writing class in 2001. I was in the Box locked down for 23 hours a day when I writing Lickin’ License, which became a #1 Don Diva Bestseller. I wrote Lickin’ License II in my cell in population while I was going to college among other things. It was a struggle for me balancing college with my writing career and other activities. I graduated Bard College in June of this year. I also spent a lot of time editing and writing everything from a screenplay and stage plays to copyrighting and business plans. It was also in prison that I taught myself graphic design. I did flyers and logos for people from behind bars. I also became very health conscious, so I spent time exercising and jogging. Sometimes I did light weights. As a member of The Nation of Gods and Earths (commonly referred to as Five Percenters) a lot of time was spent with brothers in The Nation who helped enlighten me to health issues and other educational pursuits and writing. One of my mentors is Divine G, author of Money Grip, Baby Doll and a number of other books. He helped me understand what it is to be a man and he also helped me a lot with screenwriting. Then there were other brothers in prison who were not in The Nation, but were integral to keeping my focused and challenging me to elevate my thinking. Even in the midst of the violence and ignorance of prison, there is a minority of guys that have changed their lives and are committed to progressing and preparing themselves for a productive life after prison. I found these brothers in programs like Exodus, Rehabilitation Through The Arts and Prisoners for AIDS Counseling and Education. Also a good part of my time was spent reaching beyond prison, because I adopted the motto that, “I’m in prison, but prison is not in me.” So I would write people I read about in the media, I kept pen-pal ads in on the internet and I was always trying to connect with someone doing something productive. I met my best friend Zenola through an internet ad. So I always advise men in prison to reach out of prison.

What type of obstacles did the prison authorities put in your way to deter you from writing?

The main thing that was a consistent tactic was disrupting the flow of my mail in and out of prison. This mainly happened in Woodbourne, because they were aware I had Lickin’ License and Lickin’ License 2 published. They confiscated five books Wahida had sent to me, but I got them back after I wrote a complaint threatening to sue them for violating my First Amendment rights. And I had problems receiving anything associated with my books. My manager Shock Holladay sent me a picture him and Papoose, and Papoose was holding the book. The administration didn’t let me get it. When my book made #1 on the Bestsellers list in Don Diva, they wouldn’t let me get the magazine, until I challenged them, then they ripped out the page that contained my book on it. My friend Latoya designed my website lickinlicense.net, and I couldn’t get a print out of it in totality. She had to ease snapshots of it in with her letters. Wahida sent me some bookmarks, I couldn’t get them. One of the most detrimental violations was the administration at Woodbourne literally stole a letter that Wahida had sent me in support of my release from prison. It had her company letter head (Wahida Clark Presents Publishing) and was addressed to the Division of Parole, but it was a copy for me. First, they said I had to send the letter home because it was contraband. I didn’t know what the letter was about or who it was from, I just received a notice in the mail. I found out the nature of the letter after I sent it to my people. I had it mail it back, and this time the administration literally stole it. They claimed they never received it. This was a crucial violation, because as I said earlier, it is extremely hard for guys in my predicament to make parole, so I needed all the support I could garner. Then there were the obstacles like me not being allowed to mail people press kits and books, because the administration considered it soliciting, which is a serious rule violation that could’ve landed me in the box.

The main thing that was a consistent tactic was disrupting the flow of my mail in and out of prison. This mainly happened in Woodbourne, because they were aware I had Lickin’ License and Lickin’ License 2 published. They confiscated five books Wahida had sent to me, but I got them back after I wrote a complaint threatening to sue them for violating my First Amendment rights. And I had problems receiving anything associated with my books. My manager Shock Holladay sent me a picture him and Papoose, and Papoose was holding the book. The administration didn’t let me get it. When my book made #1 on the Bestsellers list in Don Diva, they wouldn’t let me get the magazine, until I challenged them, then they ripped out the page that contained my book on it. My friend Latoya designed my website lickinlicense.net, and I couldn’t get a print out of it in totality. She had to ease snapshots of it in with her letters. Wahida sent me some bookmarks, I couldn’t get them. One of the most detrimental violations was the administration at Woodbourne literally stole a letter that Wahida had sent me in support of my release from prison. It had her company letter head (Wahida Clark Presents Publishing) and was addressed to the Division of Parole, but it was a copy for me. First, they said I had to send the letter home because it was contraband. I didn’t know what the letter was about or who it was from, I just received a notice in the mail. I found out the nature of the letter after I sent it to my people. I had it mail it back, and this time the administration literally stole it. They claimed they never received it. This was a crucial violation, because as I said earlier, it is extremely hard for guys in my predicament to make parole, so I needed all the support I could garner. Then there were the obstacles like me not being allowed to mail people press kits and books, because the administration considered it soliciting, which is a serious rule violation that could’ve landed me in the box.

Another thing obstacle that was a threat on my freedom was being issued a ticket for having Lickin’ License published. This happened after they had confiscated the five books that I mentioned earlier. The administration at Woodbourne had contacted the Inspector General (IG) in Central Office, which is the upper echelons of the prison system in New York. The IG usually comes down to investigate strikes, riots, escapes and other real serious stuff. So him coming to see me had me kind of leery. He came to interview me later, and I admitted to writing the book, having it published and expecting to receive money for it. I know the law, so I knew the Son of Sam Law did not apply unless I received $10,000 or more, and I know I had a constitutional right to have my work published. There is plenty of case law on this issue, and a good part of my time in prison had been spent in law libraries and litigating. I have settled in my favor in federal court for a case against the police who arrested me and Rodney Kinged. I had won a landmark First Amendment case against the prison system that forced them to acknowledge that the Nation of Gods and Earths was not a gang. So I knew law, and I knew the First Amendment well. But after about a month after I met with the IG, I received a ticket saying I admitted having Lickin’ License published and that I would be receiving money for it. I have never mentioned the advance I receive, just that I would be receiving royalties. This ticket was a blow, because although I knew it was factually weak, it was a Tier III, which is the classification for the most serious ticket I could get. There were guys sitting in The Box for 15 years for a single Tier III. And I was prepared to go to the parole board within a couple of years, so the last thing I needed was this ticket on my record, or to end up going to the parole board from The Box. What made the ticket week, beside the it’s not illegal to publish and profit of a book in prison, and the ticket was ambiguous in terms of what rule I actually violated. There was just the implication that I had solicited to get it published. So I went through a quick hearing, because I admitted to having it published and expecting to receive money, and I maintained that this was not a violation of any rules. More important, the ticket said I was to receive money, so even if it was a violation to receive money, I had not received any yet, according to the ticket. It was so weak but the captain who did my hearing would not submit totally because the ticket was the result of an IG investigation. So he just basically gave me a warning not to receive any money through the mail from the book. That was a relief, because as I said, I was preparing for the parole board. But these are the types of things people face as writers in prison. But I was determined to build off of my passion for writing and my focus to use it as a tool to network, irrespective of what any prison administrator said.

Why do you think they didn’t want you to write or pursue a career that could help you when you emerged back into society?

Because that old adage, “The pen is mightier that the sword.” A writer is one of the greatest threats to a prison administrator, because a writer has a voice and prison is designed to silence you and isolate you from society. With a voice, you can reach beyond the walls erected to isolate you and expose to the world things that go on in prison. So that’s a major factor. Then there is the jealousy. Many of the officers I came across can hardly write a ticket properly. So they become super haters when they see a person in prison with the ability to express themselves through the written word. You have to bear in mind that the average officer assumes the position of authority and sees the incarcerated person as nothing. Never mind that many of these officers have no other life outside of looking between men’s butt cheeks during searches and turning keys in cell gates. They’re often overweight, keep a mouth full of tobacco and ended up working in prison because of nepotism. There was a mother and daughter working in Woodbourne as officers and a father and son working in the recreation department. So when you question yourself as to who grows up saying they want to work in a prison, you know the violent nature of it and the stress it causes on employees, you realize the overwhelming majority of these people are losers with no other option but a job around people considered the worse and most dangerous on earth. So a guy like me, who because of my background in the streets, represents the dude who they were scared of as kids, and now I’m under their “rule” and reduced to a number among a small collective isolated from the world. Then because I have the nerve to write a bestselling book under some of the most oppressive circumstances, they hate me. I represent the ambition and intellect that they lack, so they ended up sniffing asses and watching men lift up their balls during strip searches for a living. They don’t want to see me succeed as a writer in or outside of prison, because I am proof of their mediocrity. It’s the same way a narcotic detective who chases down drug dealers hates to see that Jay-Z is worth almost half a billion dollars because he rapped about his experiences as a drug dealer.

How did you persevere despite the obstacles and hardships you endured?

One of my motto’s is, “When it gets hard, I go harder.” It was sheer determination and thinking before I act. I understood that my future was contingent up my present in prison, and I was willing to take calculated risks to achieve success in society. Guys told me I shouldn’t write under my actual name, because it would bring heat to me from the administration. But I know that the name Intelligent Allah had to be known in society before I reached society if I planned to be successful there. So I took a calculated risk. Any successful businessperson will tell you part of their success is do to calculated risks.

How does it feel to accomplish what you did from prison?

Great! It’s a testament to the fact that you can think your way out of any situation. I spent many nights in my cell analyzing moves to make. Instead of running the yard all day kicking the Wille Bobo, I was in the yards, schools and libraries bouncing ideas off of guys about writing, business and life after prison. Then there were the countless hours I spent taking writing courses and studying writing books and books on the publishing industry. So the success I have had, which is nothing compared to where I plan to go, is a blessing and proof that dedicating time and energy can pay off if you are persistent.

What are you doing now and what projects are upcoming?

What are you doing now and what projects are upcoming?

Right now I’m doing everything. I’m tightening up two ebooks I’m going to drop to hold the readers that are loyal to me over until I put out Sex Cells. You’ll also see some work under my alias Vance Burrows. I’ve been getting people familiar with the name through my Vance Burrows Facebook page. I’m still editing independently and I’m also doing graphic design work with my brand Koozi Graphics. I just did a flyer for underground rap artist Crown Vic, who is a close friend of mine and I did a logo another company called Impervious Entertainment. You can check some of my work on Facebook at Koozi Graphics. I’m working on redesigning lickinlicense.net also. I also have the Lickin’ License Group on Facebook. So things are moving along. I also look forward to working with Gorilla Convict. That’s really an honor, because outside of watching Wahida hustle when she was incarcerated, I don’t know any writer who was more inspiring to me than Seth Ferranti.

What advice do you have for prison writers?

Study the craft of writing and study the game, because you need to hone your skills to get in the game and you need to understudy the publishing industry so when you get in who know what’s what. And of course, don’t let anyone deter you from reaching your goals. There are going to be people who don’t see your vision, but as long as you see it you can make it a reality. And lastly, write as much as you can before you come home, because making time out here is far harder than when you are inside. Trust me.

Check out http://lickinlicense.net

2 Comments

That was real talk, I know Homey personally from being down myself and can attest to seeing some of his growth artistically and generally. He is definitely a real dude, and a great writer, so I commend his success. Many cone from where we come from, but only few are chosen. Keep doing your thing .

Vance and I have been friends since we were kids. We grew up in the same dangerous streets in ENY. You will never know your path in advance. Sometimes I wonder where we (my ENY family) would be, if not right where were are today. Vance was (as you would say) locked up for most of his youth. The crazy twist is, he wasn’t locked up because a talent he probably would have never found was freed. I’m not saying going to jail was a good. I’m saying going to jail does not have to break you, lessen you, steal ALL your freedoms. The freedom to still have the will to BE and EXIST is what I see when I look at my brother Vance. What a great writer and a huge inspiration to us all. I love him.